“Today in Iran, one must either agree with the mullahs or be condemned. This is not Islam; this is religious fascism.” – Shapour Bakhtiar, Former Iranian Prime Minister. (From a 1980 interview in exile in Paris).

The recent death and destruction that struck a tranquil Nepal is a grim reminder of what Bangladesh endured just over a year ago. In both cases, it was not merely so-called Gen Z activists or ‘riff-raff” on the streets; legitimate grievances were weaponized by organized political forces—both domestic and foreign—to bring down governments.

However flawed, both governments had constitutional legitimacy; however corrupt, they remained subject to public scrutiny; and however authoritarian, both resisted the unchecked rise of religious extremism.

In Bangladesh, the events of July–August 2024 initially appeared to be a genuine people’s movement. Crowds from all walks of life joined in; even children of ruling-party elites defected. The demands were cloaked in secular language, the slogans wrapped in patriotism, and the songs echoed the spirit of 1971—only for an entire generation to discover, after that fateful August of 2024, that radical forces had deceived them.

For a government that had presided over unprecedented economic growth for 17 years, the sudden collapse was both shocking and destabilizing.

Nepal’s trajectory diverged from Bangladesh’s in one key respect: the organized presence of Islamist forces. In Bangladesh, Islamist networks never reconciled with the secular ideals of the Liberation War. Nurtured under military regimes in the 1970s and 1980s, and later tolerated by mainstream parties, these groups entrenched themselves in social and educational life.

Ironically, Sheikh Hasina’s liberal policies of inclusion—making it easier for madrasa graduates to enter universities—ended up creating the perfect ecosystem for Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) and Hizb ut-Tahrir (HT) to thrive.

These groups groom impoverished madrasa kids from childhood, only to unleash them later as politically charged foot soldiers. They were the shock troops of the July–August upheaval, and their rise is now glaringly visible in the student union victories at two of Dhaka’s most prominent universities.

In Bangladesh, Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) and its allies emerged as the main beneficiaries, exploiting the chaos to consolidate their grip.

This trajectory bears an ominous resemblance to Iran’s 1979 Revolution. There, secular and moderate leaders such as Mehdi Bazargan and Abul Hassan Banisadr initially led the push for change, only to be sidelined, exiled, or killed as clerical forces consolidated absolute power under Ayatollah Khomeini.

Bangladesh today shows disturbing parallels. The current administration — illegal from a constitutional standpoint — cannot be described as Islamist in its composition. Many of its figures are Western-educated and secular in worldview.

Yet, like the liberal Iranian leaders who found themselves beholden to clerical militias, today’s rulers in Dhaka depend on the organizational muscle of Jamaat-e-Islami and Hizb-ut-Tahrir.

Since Sheikh Hasina’s fall, JI-led radical Islamists have forged an alliance with madrasa-trained preachers and opportunistic politicians.

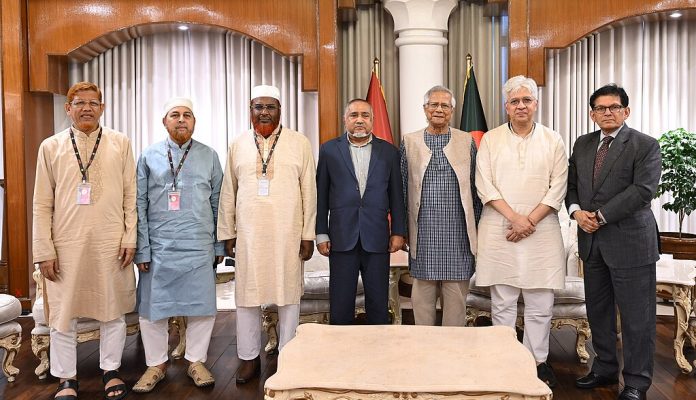

Meanwhile, Nobel laureate Dr. Muhammad Yunus — once hailed as a reformer by the West — has presided over an administration from the beginning associated with mob rule, opportunism, and appeasement of Islamist youth.

Ironically, while he accuses Sheikh Hasina of ‘fascism,’ his own rhetoric reveals expansionist ambitions laced with religious extremism.

Yet hope is not lost. Many Bangladeshis now recognize that, despite numerous flaws, the previous secular administration of Sheikh Hasina provided stability, growth, and a bulwark against extremism. More importantly, they now see that surrendering to Islamist dominance risks dragging the nation into an Iranian-style abyss — where every choice, from dress code to diet, falls under theocratic diktat.

The road back will be arduous. Awami League and BNP, which together commanded nearly 80 percent of the electorate since 1991, are shadows of their former selves. BNP’s corruption and policy failures have made it politically toxic.

Political observers suggest that U.S. efforts to facilitate the BNP’s return through a “managed” election in 2026 face significant challenges. Recent meetings in Qatar and London indicate that such attempts may be losing momentum.

Bangladesh now stands at a dangerous crossroads. Without an inclusive political process, the vacuum will only empower radical forces that threaten both the country’s democratic fabric and the region’s stability.

For the United States, Bangladesh is not a distant concern — it is a nation strategically located between South and Southeast Asia, at the heart of key maritime routes, and central to counterterrorism, supply-chain security, and regional balance.

What is urgently needed is a credible caretaker government that ensures free and fair elections, allowing all major political parties — including those with long-standing roots in Bangladesh’s democratic struggle — to participate without fear of intimidation or exclusion.

Only through such an inclusive process can the people’s will be genuinely reflected and extremist elements contained.

For Washington, the choice is not about favoring one party over another, but about securing a partner in Dhaka that is capable of governing effectively, maintaining regional stability, and aligning with shared security interests. A government born of exclusion and repression will not last; one elected through a transparent process stands a far greater chance of preserving Bangladesh’s founding values and serving as a reliable partner to the United States.

But if Washington falters and Dhaka follows Tehran’s path, it may be decades before the dawn of democracy is seen again. As Shapour Bakhtiar warned, ‘No democracy can survive when it is governed by those who claim to speak on behalf of God.’ The lesson is clear: hesitation today could imperil Bangladesh—and U.S. interests in the region—to a long night without freedom.

Rana Hassan Mahmud

Rana Hassan Mahmud is a Bangladeshi American political analyst who writes for leading Bangladeshi dailies. An Engineer by training, he studied at Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET) and University of California, Irvine. He is a human rights activist.